Independent-ism in the 2024 Election

With a raft of politicians aiming to break free from their parties - whether in name or not - what do recent elections tell us about their chances?

At the election in July, many MPs are looking to break free from their parties and stand on their own two feet. Whether they are disgruntled, excluded Labour MPs, or Conservative MPs aiming to save themselves from the coming rout, ‘independent-ism’[1] seems to be a theme. Will it work?

Mayoral races, such as those seen only a couple of weeks ago, can be a good indicator as candidates can be ‘quasi-independent’, running highly personalised campaigns. Andy Street, the incumbent West Midlands Combined Authority Mayor, ran significantly ahead of his party – which seldom appeared on his campaign materials[2]. Ben Houchen, ditto. Indeed, actual independent candidates in the 2024 local elections did relatively well. Jamie Driscoll, the sort-of incumbent for the newly formed North-East Mayoralty, ran as a left-wing independent after losing the Labour selection, gaining a respectable 28% of the vote.

This is impressive, and perhaps shows that there is an appetite for independent-ism at elections. However, eagle-eyed readers will notice that of these three, only one actually won, and Houchen’s 2021 result in the Tees Valley Mayoral Election was an unassailable 72.8% - a high base to come down from.

Another telling case (and I say this without bias as a proud East Midlander) is that of the East Midlands Mayorality. The Conservative candidate, Ben “two jobs” Bradley, cuts the figure of a local ‘big man’, being the MP for ‘red wall’ Mansfield and the leader of Nottinghamshire County Council. Even with this record, he came up short and ran basically level with his party in the region[3].

Mayoral elections are those in which you would expect independent or quasi-independent candidates to do well. Turnout is low, with a ‘high turnout’ typically being anything over 30%, so the electorate are definitionally a pool of higher-engagement voters.

Importantly, they are highly ‘presidential’ contests, dominated by a figurehead with a distinct record and platform, without national repercussions per se. If candidates aiming to break free from the party system, either by running as actual independents or by aiming to present themselves as such, do not win in these circumstances, it does not bode well for the slate of independents and quasi-independents running in the July election.

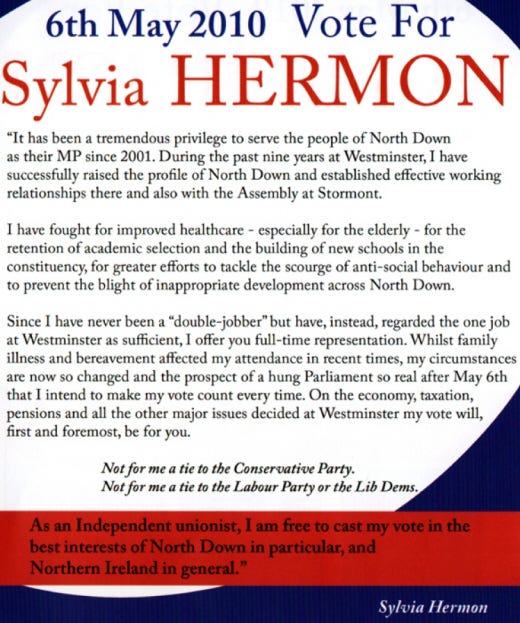

Perhaps Jeremy Corbyn, Claudia Webbe, George Galloway, and the Conservative MPs that will try to defy gravity can look to Sylvia Hermon – who was repeatedly elected as an independent candidate in North Down at general elections after resigning from the Ulster Unionist Party. Though, the dynamics of the Northern Irish Unionist vote and the fact her old party stood down in the seat probably make this a special case.

Or, perhaps they would be better served by looking to the wide array of independent offerings in 2019 – with ex-Conservative remainers, notably David Gauke and Dominic Grieve; Change UK MPs, such as Anna Soubry and Chris Leslie; and newly-minted Liberal Democrats, from Heidi Allen to Luciana Berger. All of these candidates, independents and quasi-independents running personalised campaigns on a salient national issue, lost.

I may be wrong – Jeremy Corbyn may be able to use his national profile and well-organised local operation to edge out Labour in Islington, Claudia Webbe could successfully use the ongoing war in Gaza to motivate pro-Palestine voters in Leicester East, George Galloway – perennial winner-then-loser – might find that a janus-faced campaign works again.

However, in politics, gravity is everything. Voters are simply not as engaged as politicians like to believe. If parties are able to dominate in highly personalised races at 30% turnout, then the remaining 30-40% of voters (who will be comparatively less politically informed) that will turnout at the general election (an electoral event in which voters choose a party for government, rather than a person for a mayoralty) will be much more likely to vote at the pull of national forces. Independent-ism likely won’t work, and (quasi-)independents will be forced down to earth.

[1] This is a horrendous ‘word’. I can only apologise.

[2] Street received 49.8% of the two-party vote, whereas the Conservative Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC) candidate (a much more generic ballot offering held on the same day) in the West Midlands received 42.5% of the two-party vote. I am using two-party vote as the comparison here, as the PCC election had only Labour and Conservative candidates.

[3] Ben Bradley received 28.8% of the vote, Conservative Police and Crime Commissioner candidates in the East Mids received 31.6% (not using two-party vote here!).